YA Pride: Interview with Emily M. Danforth

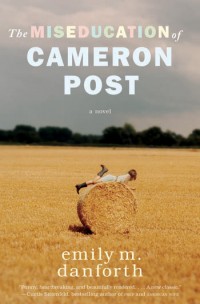

Earlier this year, NPR invited me to review a debut young adult novel. I was hesitant at first because while I used to review many things for a living, since I became an author I've stopped doing that. However, the book — a story about a girl coming of age and coming out in Miles City, Montana, in the late 1980s/early 1990s — seemed intriguing enough that I wanted to give it a try. I'm so glad I did, because that book, The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth, soon became one of my favorite reads of the year.

When I decided to do this YA Pride series of posts, I knew immediately that I had to ask Emily if she’d agree to an interview. I was so happy when I received her responses, because they’re as full of detail as her novel. My questions about Emily's experiences in publishing Cameron Post resulted in some wonderfully thoughtful and thought-provoking responses about homophobia vs. heteronormativity, the differences between coming-out and coming-of-age novels, and more.

Earlier this year, NPR invited me to review a debut young adult novel. I was hesitant at first because while I used to review many things for a living, since I became an author I've stopped doing that. However, the book — a story about a girl coming of age and coming out in Miles City, Montana, in the late 1980s/early 1990s — seemed intriguing enough that I wanted to give it a try. I'm so glad I did, because that book, The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth, soon became one of my favorite reads of the year.

When I decided to do this YA Pride series of posts, I knew immediately that I had to ask Emily if she’d agree to an interview. I was so happy when I received her responses, because they’re as full of detail as her novel. My questions about Emily's experiences in publishing Cameron Post resulted in some wonderfully thoughtful and thought-provoking responses about homophobia vs. heteronormativity, the differences between coming-out and coming-of-age novels, and more.

Malinda Lo: I don't know if you've noticed this while promoting your debut novel, but I find the most frequently asked question I get is some variation on, "How difficult was it for you to publish an LGBT novel?" So I'd like to ask you: What was your publication process like? Did you experience any homophobic pushback from the publishing industry? If so, how did you deal with that? And if not, how do you feel about getting asked this question?

Emily M. Danforth: Oh yes, oh yes, I’m quite familiar with this question. I mean, the thing is: it’s not so easy to publish one’s debut novel (if the writer in question isn’t a celebrity or a name of some kind). I know I’m not saying anything terribly surprising here, but publishing a novel just isn’t the world’s easiest task, there are a lot of moving parts. So, keeping that in mind: it was no more “difficult” for me to publish The Miseducation of Cameron Post than it is for any debut novelist to get her/his somewhat “quiet” coming-of-age novel published.

In fact, the specifics of Cam’s “miseducation” — her time in conversion/reparative therapy, that is — actually probably made the book more saleable than less, simply because it’s an intriguing and unfortunately timely topic. My experiences with everyone who worked on the publication of this book were overwhelmingly positive and supportive, and never once was I asked to tone down or change content because it was too controversial or risqué or what-have-you. There was simply no “homophobic pushback” anywhere in the process (as I’m aware of it, anyway).

I think questions of this nature are so popular right now at least partially because of the YA agent “de-gaying scandal” from the fall (and the many, many ensuing online conversations about the particulars/veracity of that event/series of events). They’re also popular because there certainly are fewer YA novels with LGBTQ identifying characters (or themes, content) than there are with straight characters, and so I think sometimes people want to make a linkage there — beyond the less exciting truth that there are just a whole lot fewer of these novels being written in the first place.

It’s tempting to create a kind of narrative of blatant homophobic bias that, in my experience, simply isn’t very truthful to the landscape of contemporary publishing. Heteronormativity is not, in and of itself, a very satisfying or specific target on which to blame the lack of LGBTQ content in YA novels, but it’s a much more accurate reason that we see fewer of these novels than is focusing on the perceived homophobic bias of any individual agent, editor, or publishing house.

I’m much more interested in where all of these questions about LGBTQ novels and possible bias or pushback lead, which is, to my way of thinking, to a series of questions about just what the heck LGBTQ fiction is, anyway? Who/what defines it? What are the parameters and how do we construct and (maybe more to the point) market those parameters? Does the inclusion of a non-straight protagonist make, necessarily, for an LGBTQ novel? What about a heterosexual protagonist but four LGBTQ identifying side characters? How much of the novel’s “aboutness” must concern the character’s romantic relationships for it to “count” as an LGBTQ novel? If a book pushes against any aspect of heteronormativity is it, necessarily, an “LGBTQ book?” Where are the lines drawn and by whom and for what reasons?

Whatever (messy) answers we might come up with for these questions today, I feel very confident they’ll seem pretty antiquated in just a few years. I’m hoping so, anyway.

ML: This is a very interesting point here and I just want to clarify: Are you saying that you think heteronormativity, rather than direct homophobic bias, is the reason there are so few YA novels published with LGBT characters? I think this is a really useful idea. Can you explain a bit what heteronormativity is and how it might contribute to the current LGBT YA landscape?

EMD: Yes, I am saying that heteronormativity plays a larger role, a more significant role, I think, than direct homophobic bias against novels with LGBTQ identifying characters (or themes, situations, etc). This isn’t to suggest that such bias mightn’t also occasionally be present, but I just don’t think it’s nearly as prevalent.

As far as saying a bit more about it: I’m going to try to do this somewhat succinctly (not so much my style) and therefore will offer a handy definition from a booklet that the Graduate School at Syracuse University put out a few years ago. (You can find the full booklet here. Also, if you’re interested in the genesis of this term/queer theory in general, believe it or not the Wikipedia page on heteronormativity is not a bad place to start.)

Okay, so here goes:

“As a term, heteronormativity describes the processes through which social institutions and social policies reinforce the belief that human beings fall into two distinct sex/gender categories: male/man and female/woman. This belief (or ideology) produces a correlative belief that those two sexes/genders exist in order to fulfill complementary roles, i.e., that all intimate relationships ought to exist only between males/men and females/women. To describe a social institution as heteronormative means that it has visible or hidden norms, some of which are viewed as normal only for males/men and others which are seen as normal only for females/women. As a concept, heteronormativity is used to help identify the processes through which individuals who do not appear to ‘fit’ or individuals who refuse to ‘fit’ these norms are made invisible and silenced.”

When I talk about heteronormativity as it might affect the publication of LGBTQ YA novels I’m speaking mostly about a kind of cultural silencing of a variety of gender identities/expressions and sexualities that don’t conform to the binary discussed above. When there’s this kind of bias built into our very culture (and certainly there is) — our laws and systems and practices — it’s not simply a matter of editors or publishing houses and any (possible) individual biases against LGBTQ characters or content — it’s so, so much larger than that.

Though things are changing for the better (unquestionably, to my mind), I think it’s still true, widely, that anything that confronts or confounds heteronormativity is immediately “othered” (as in it’s considered “different,” “not the norm,” “its own thing,” “weird” — you get the idea) by many, many people. So if a novel has a queer character, say, even folks who might embrace that character or storyline or what-have-you often will still “other” it, as in recognize it as something “other than” what is heteronormative, as “oh, that’s the novel with the lesbian romance” or the one with the “bisexual football player,” etc.

In other words: the novel’s LGBTQ content so often becomes its primary identifying feature. Thinking of heteronormativity as most people’s default assumption/stance can be a useful way of getting a handle on it.

Sometimes thinking like this can be useful for marketing, say, or finding a particular audience, but when we think about how books are selected for publication it seems obvious, to me, anyway, that this kind of binary thinking — this privileging of that which is heteronormative — is much more responsible for fewer LGBTQ books/characters than is overt homophobia.

ML: In YA fiction in particular, the coming-out story is a tale that has been told many times and in many different ways. Do you feel that The Miseducation of Cameron Post is a coming-out story? Why or why not?

EMD: No, I don’t personally think of Cam Post as a coming-out story. It’s fine if readers do, and I even understand that impulse. I just happen to think that body of LGBTQ lit is usually dismissed or even sneered at, now, as passé or overdone: clichéd. (Not that sneering has every stopped me before). I think there’s just more potential, more room, maybe, in thinking of this novel as a coming-of-age story. (What I often say, jokingly, to get at both of these things, is that I wrote a “coming-of-GAYge” novel.)

EMD: No, I don’t personally think of Cam Post as a coming-out story. It’s fine if readers do, and I even understand that impulse. I just happen to think that body of LGBTQ lit is usually dismissed or even sneered at, now, as passé or overdone: clichéd. (Not that sneering has every stopped me before). I think there’s just more potential, more room, maybe, in thinking of this novel as a coming-of-age story. (What I often say, jokingly, to get at both of these things, is that I wrote a “coming-of-GAYge” novel.)

I suppose some people might think that I’m quibbling here, and maybe I am, but I’m wholly enamored of the literary tradition of the American coming-of-age novel, which usually features a protagonist making sense of the world and her place in it from a young age. I love these kinds of books. I return to them again and again.

If you think about the classification broadly, and I do, the "coming-of-age novel" covers a wide range of styles and approaches, from Junot Diaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao to Jane Fitch's White Oleander to Jeffrey Eugenides' The Virgin Suicides, or Rita Mae Brown's Rubyfruit Jungle and Marilyn Robinson's Housekeeping. And the titles I've listed barely scrape the surface. These books have been sold to adults and to teens, as literary fiction and as popular fiction. Some of them, like Nick Burd's excellent The Vast Field's of Ordinary, have been sold and marketed as YA, many others have not.

I think I resist the classification of “coming-out” novel because it seems to suggest that my book is reducible to one essential element of the story — it makes it a “problem” novel. All novels have problems, of course, but I hate to think of Cam’s misadventures as reducible to one element.

I’m always offering Flannery O’Connor quotes in interviews, but it’s true that I subscribe to so much of her advice about the writing of fiction. As she put it: “You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anyone asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story.” If someone says: “Oh, Cam Post is just another coming-out novel,” well, that hurts, mostly because there was just so much about the experiences of growing up and falling in love (and in lust), and forming/finding/seeking out identity, and innocence giving way to experience, that I was trying to “get at” in this novel that reducing it to Cam’s “outing” and its aftermath feels like not nearly enough.

ML: There are many elements of Cameron Post that made me feel it could have been published as an adult novel. What made you decide to publish the novel as young adult fiction?

EMD: I wanted to find an audience, pure and simple. I wanted Cam’s story to be read and, hopefully, to then be really meaningful to at least some of its readers. Publishing it as YA seemed the very best way to make all of that happen.

I’ve made no secret of the fact that when I write fiction I absolutely don’t write with an audience peering over my shoulder: I just can’t, I’d get nothing down on the page ever. I write for an audience of me. So this book wasn’t written “as or for” YA, but it wasn’t not written that way, either. Does that make sense? It was simply written as a first-person coming-of-age novel. That really is the only way I thought of it during the entirety of the drafting process.

But later, while trying to publish it, I thought much more specifically, strategically, even (which I suppose sounds sort of gross but is honest), about just how much a book like this would have meant to me as a closeted fourteen-year-old in Miles City, Montana. (Well, I mean: the book is set there, of course, so, that would have been pretty darned meaningful, but you get what I’m saying, here). If we read novels, or if some of us read novels, anyway, to, as C.S. Lewis said, “know that we’re not alone,” to see our selves and lives (or potential versions of selves and lives) reflected and refracted back to us, then the idea that Cam’s journey might offer those experiences to teenage readers is wholly thrilling to me, particularly because I was absolutely one of those teenagers who (like Cam) was so hungry (desperate, even) for LGBTQ representations in the culture around me.

ML: Do you have any sense of whether your readers tend to be adults or teens? Have you noticed any common themes in their responses to Cameron Post?

EMD: My sense, thus far, is that Cam Post is getting a pretty incredible mix of both teen and adult readers. I mean, lots of adult readers are now reading YA anyway, right? But some of the reviews in various media outlets are undoubtedly helping the book find its way into the hands of some adult readers who maybe don’t (or haven’t yet) read that much YA. (One of the earliest Cam-related emails I received, actually, was from a forty-something, straight, married father of two from New Jersey, who, incidentally, bought the book after reading your NPR review, Malinda. So, you know: thanks again for that. Sheesh do I owe you one.)

(ML: No problem! I’m always pushing books I love on total strangers.)

EMD: I’ve received several really wonderful emails from readers in “those big, square states out west,” and most of them talked about the ways in which their own experiences as closeted teens aligned with aspects of Cam’s experiences (for good and bad). Some of those readers have been adults, but some of them are either currently teens or they’ve just barely hit their twenties. I’ve also heard from lots and lots of readers who knew me in high school and are trying (unsuccessfully, might I add) to “tease out” the most autobiographical elements (they think) from the novel.

But the most common theme showing up in various readers’ responses to the book (at least for those readers communicating directly with me via my website/FB/twitter/or in-person) is that people really want to know what happens after that final scene at Quake Lake. (I don’t think that’s really a spoiler of any kind in my mentioning that final scene. I hope not…)

They want to know where Cam goes from there, and also what happens to Jane and Adam. And what about Margot? And what about Irene? I’ve gotten at least a few dozen “demands for” a book two, and also one or two emails asking really, really specific questions (and wanting specific answers) about potential plots for Cam’s future. That’s all very flattering, of course, but mostly it makes me appreciate just how invested some readers were in this world I created on the page.

ML: What are you working on now?

EMD: I’m working on a couple of novels. The first is (tentatively) titled Well, Well, Well… It follows one copy of the infamous and historically banned novel, The Well of Loneliness, from the day it comes off the press in London in 1928 and is picked up by its author, the colorful Radclyffe Hall, to the day it — well, I can’t say what happens to it, but suffice it to say that we follow this copy of the book as it passes hands from one character to the next for 100 years.

The characters are mix of fictionalized versions of “real people,” like actress/provocateur Tallulah Bankhead (who was friends with Hall), and also those who are complete inventions. The structure is kaleidoscopic, with this individual copy of Hall’s novel as the fulcrum around which these various narratives and worlds collide. However, some sections also make use of material from The Well of Loneliness, reshaping or altering particular scenes or moments from that book so that they comment on the action in my novel.

The other novel is a contemporary YA book (with interspersed historical sections) that follows some adolescent actresses on the set of a controversial film. I won’t tell you anything more (yet) other than that, in my dream world, it will be published under the title CELESBIAN! (All caps with the exclamation point).

>>>

As part of my YA Pride celebration, I'm giving away a copy of Emily M. Danforth’s The Miseducation of Cameron Post to one lucky winner! The book has received four starred reviews and a very rare review from me.

The fine print:

- To enter, simply enter your email address in the Rafflecopter widget below so that I can contact you if you win.

- The winner must be able to provide a valid United States mailing address where he/she can receive the prize.

- The deadline for the Miseducation of Cameron Post giveaway is June 19, 2012!

- Winners will be notified by email, and prizes will be mailed in July 2012.