Write from the gut, not from fear of prejudice

The other day I was on Twitter when an #askYAed discussion popped up. (In case you don't know, that's the hashtag that some young adult editors use when they begin a Twitter chat in which anyone can ask them questions about YA publishing.) So I clicked on the hashtag and lurked a little. Usually at these things, it's not too long before someone asks about trends in YA ("Is paranormal romance really over?") or about how hard it is to get something published ("Do boy books not sell?" or "If I have a main character of color/LGBT main character, does that make it harder to find an agent/publisher?"). I've heard these questions plenty of times before. They are perennial favorites, and not only during #askYAed. I'm asked these questions at conferences, too, and people sometimes email me directly to ask, "How hard is it to publish an LGBT YA book?" I've already answered that with my own experiences here, but now I realize there's something else I want to say in response to this widespread belief that publishing (or The Powers That Be, whoever they are) is biased against stories that fall outside the mainstream straight white norm.

Yes, racism, homophobia, and heteronormativity exist. But you cannot let perceptions of other people's prejudice limit what you write or create.

If you're a writer of any sort (aspiring, about to be published, published multiple times), the most important thing you can do is listen to your creative gut. If it wants to tell a story about a disabled queer person of color, then you go ahead and do it. Maybe some people will be more hesitant to publish it, but you know what? You don't want to work with those people. You want to work with people who support your vision and are allies in your cause. Those people exist. Your job — and your agent's job — is to find them.

Yes, there are people in the business who are afraid to publish things outside the norm. I have encountered them. I have been rejected by them. Does it make me want to make my work more mainstream (i.e., straight)? No, it makes me angry, because those people are insulting me (a queer person of color) personally when they make business decisions based on a belief that stories about people like me aren't viable in the market. It also makes me sad that some people are still so limited in their thinking.

However, I never give more than five minutes' thought to these folks' opinions, and you shouldn't either.

You — the writer — don't need to limit your own thinking the way these naysayers limit theirs. Your job as a writer is to think as far outside the box as you need to, in order to tell the story that wakes you up at night. Your job as a writer is to focus on that story and find the absolute best way to tell it, regardless of what the "mainstream" may believe.

I'm not saying you shouldn't listen to your critique partners or editors when it comes to craft. Of course you should listen to them; part of the way you tell your story the best possible way is to work on your craft and become the best writer you can be. But when someone says, "I don't think your character should be black because that will turn off white readers," obviously your response should be, "So what." If someone says, "Queer characters never sell books," your response should be, "So what." If someone says, "Nobody wants to read about disabled people," your response should be, "So what."

People will have those responses. But your job is to not listen to them. If you listen to them, you are silencing yourself.

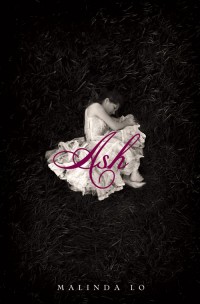

I'm saying this to you because I've gone through this myself. Before Ash was published — before I even found an agent — I had to deal with my own internal doubts about telling a story about a lesbian Cinderella.

I'm saying this to you because I've gone through this myself. Before Ash was published — before I even found an agent — I had to deal with my own internal doubts about telling a story about a lesbian Cinderella.

As I've said many times when I talk about the origins of Ash, the first draft involved Ash falling in love with Prince Charming. It wasn't until I asked a good friend to read that draft that I realized I was telling the wrong story. My friend pointed out (very kindly) that Ash didn't have much chemistry with the prince; in fact, she seemed to like this other character a whole lot more…and that character was female.

When I reread the first draft, I had to admit that my friend was right. It was so obvious that the story I wanted to tell was different than the one I had forced myself to write. But if I told the story I wanted to tell, that would mean I'd be telling a lesbian Cinderella. At the time, back in 2003 and 2004, the concept of a lesbian Cinderella seemed completely strange to me. It seemed so bizarre and so foreign because I had never read a book like that before. And I was convinced that it would make Ash unsellable.

However, I knew in my gut that this was the story I wanted to tell. Back then, I had recently begun a career as a freelance writer, and I was freelancing for a growing number of LGBT publications. I had just begun writing for AfterEllen.com, and I was living in San Francisco, surrounded by a wonderful and supportive lesbian community. I'm sure that the community I was in, my amazing friends, and writing for AfterEllen helped me to take the leap. Ultimately, I decided to do it.

On Friday, Oct. 1, 2004, I sat down with my writing journal and wrote this about Ash: "I have a problem I need to work out: I'm going to turn it into a lesbian Cinderella. That's what wants to happen; I've just had to accept it."

While there were plenty of hurdles I had to go through during the revision process (plot! structure!), once I accepted the fact that Ash was falling in love with a female character, the romance was no longer an issue. The chemistry between Ash and her love interest was clear, and after I started down that path, I was never tempted to look back.

I can't remember if I felt nervous about submitting a lesbian Cinderella to agents. By that time, I'd revised Ash at least one more time, and my career at AfterEllen had taken off. Every day, I was surrounded online by queer women who were hungry for more representations of queer women in the media they loved, and I knew that my book would have an audience.

Now, I'm not telling you this story to prove that getting a book about a queer character published is easy. Getting published in general is not easy, and sure, some things may make a manuscript a harder sell to some editors. But you know how you can make your manuscript stand out? It's really pretty simple. Write the best book you can. Work hard on your craft. And tell a story you believe in.

In many ways, this goes against the majority of what we're told about capitalism, marketing, and promotion. But I have to break it to you: Creative writing is not a lucrative field; it's an art. ((This is why most writers have day jobs! I did when I was writing Ash, which made it possible for me to pay the rent and write a book I loved after work.)) There is no way you can focus group your way to a genuine, heartfelt story. The only way to get there is to listen to your gut — and your heart — and do what it tells you.

So this is what I think you should say when people tell you it's harder to publish a book with non-"mainstream" themes or characters: SO WHAT. And then go back to your computer or notebook and finish that novel.