On agendas, social issues and real-life awkwardness

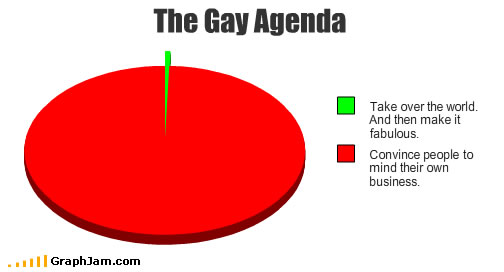

Last month, when I blogged about Heteronormativity, fantasy, and Bitterblue, the issue of a writer's "agenda" popped up more than once, as in: Did Kristin Cashore have a liberal agenda when writing Bitterblue, and was it too obvious? Those questions can obviously be extended to all writers and books: Did the writer have an agenda (of whatever kind), and was it too obvious? I've been thinking about this issue ever since, and today I'm going to unpack some of my thoughts about it. First, let's think about the term agenda. An agenda is a list of action items: something that someone wants to see accomplished. That's not a political definition, but the term "agenda" certainly has become highly politicized in contemporary American culture. "Agenda" is often used disapprovingly, to indicate that the speaker does not agree with those action items. Probably the most famous usage of this kind is the term "gay agenda."

I often get the feeling that unless you're talking about a list of things to do during a meeting, nobody uses the word agenda unless they disagree with what's on it, or unless they're satirizing that kind of usage. Basically, the word agenda is really, really loaded. That doesn't mean the word shouldn't be used, but it should be used carefully and with full awareness of all the negative connotations it entails. Additionally, when the word agenda is used to critique a novel, it's often used while making assumptions about the author's intentions. Very, very few readers know what the author's intentions were, though it's super easy to slip into guessing. I've done it!

But because I want to talk about agendas apart from intentionality, I'm going to move away from the term agenda entirely. I think it's a bit more constructive and helpful to think about this subject a different way. Luckily, a commenter at that heteronormativity post said it best:

Lcasey3 wrote in the comments: "It’s a fine line that I’m sure writers come across all the time – how do you make social issues a part of your story without hitting the reader over the head?"

First: social issues. What are they? Initially it might seem obvious. Poverty, racism, sexism, gun violence, etc. But — and this is a big but — one person's social issue (let's say same-sex marriage) is another person's daily life (whether or not they can get legally married). "Social issue" can carry a certain stigma because it can suggest a problem to be solved. Not everyone is going to agree that the issue at hand is a problem, or that it should be solved if it is a problem. (See current discussion on gun violence in America.)

Second: there's an implicit assumption in the question (and in the discussion at the heteronormativity posts) that a writer might be able to avoid writing a story with social issues in it. But I don't believe that's possible.

Every story has social issues, because stories are about social experience. As I pointed out above, what constitutes a social "issue" as opposed to everyday life is truly a matter of perspective. Even if the writer believes they're writing a story devoid of "social issues," I guarantee you that from a different perspective, it's probably chock full of them.

This is because social issues are largely identified by how they mark difference. Something becomes a social issue when it's not the mainstream norm. That's why gay rights, not straight rights, are often seen as a social issue. That's why racism in the United States is about discrimination against people who are not white.

If someone believes their work is devoid of social issues, that means they believe their work hews 100% to mainstream social norms. In America, that means their work is about white, middle-class, straight, able-bodied individuals who live in nuclear families. But while this may be the norm, it's not the reality. The really disturbing thing is, every deviation from that norm can be categorized as some kind of social issue.

That's why I think it's extremely unlikely, if not impossible, for a writer to write a story that has zero social issues in it. And if the category of "social issue" itself is a matter of perspective, what is a writer to do if she wants to avoid "hitting the reader over the head"?

The problem is, no writer can predict how every reader is going to respond. Something that seems heavy-handed to one reader will be entirely missed by another. (See: viewers' reactions to Rue of The Hunger Games being played by a black actor.) As author Kate Elliott commented at the Bitterblue piece, "Sometimes I think I, as the writer, write toward the person who I think is least likely to 'get it' and thus all the readers who do 'get it' may feel it is a bit obvious. I’m not sure what to do about that."

It strikes me that there's a range of acceptability when it comes to heavy-handedness. If your novel is about politics, the reader is likely going to expect you to deal with "social issues" and may in fact be ready and waiting for those issues. In my opinion, science fiction (especially dystopian sci-fi, which is basically political fiction) and fantasy (which often involves creating entire new worlds that are basically blank canvases for social issues as metaphor) are also especially friendly to social issues. Good world-building will embed those social issues in a way that seems completely natural, even though they're entirely artificial.

Crime fiction also involves social issues, often overtly. The investigation of crimes, the police system, the courts — these are all places that invite an engagement with real-world issues. Although romance might seem to avoid social issues because it's often about escapism, I think that romance also engages directly with them, especially in terms of women's roles and the family. This is a huge source of conflict in our world today, and romance is right there in the middle of the discussion. Even literary fiction (or maybe especially literary fiction) engages with social issues — class, war, race all have novels focused directly on them.

But let's say you're not writing a book that's directly about a social issue (even though it may be indirectly about one). Let's say all you want to do is make it clear that somebody's gay or black or disabled or simply doesn't come from a privileged background. Let's say you don't want their non-mainstream identity to be an "issue"; you want it to simply be. To exist as part of their character.

Then you have to introduce them to the reader, and this is where you will inevitably trip up. At this point in time, in the contemporary United States, I honestly don't think you can write something about race, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability that will be understood the same way by every reader. While a writer's skill may reduce the number of misunderstandings, it can't eliminate them, because real life will always intervene. A reader always reads a book through the filter of their real-life experience; they're likely comparing the story, consciously or not, to situations they've experienced. And real life, especially when it comes to recognizing difference, is inherently imperfect.

I don't know about you, but I often find real life pretty damn awkward, and nowhere more so than when I engage with a real person's race, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability in real time, in real space, for the first time. When I'm talking to old friends and there's a history of comfort and security in talking about these things, it's less awkward. But the first time I'm meeting someone, there will always be a silent, self-conscious monologue in my head: This person is male/female, white/not white, gay/not gay.

Would I say it out loud? Probably not, unless I was pointing them out, from across the room, to someone I know: "I'm talking about the Asian guy at the bar." And even then, I will internally flinch a little at using the word "Asian." In fact, I would probably only use it because I'm Asian. If the person was African American, I bet I'd avoid using the term "African American" because I wouldn't want to seem racist, even though all I'd be doing is trying to describe them.

This is because we live in a time when race (etc.) is highly politicized and highly nuanced and highly, highly charged. I don't think that's a bad thing. I think it's good that we're in a time and place when we're forced to be aware of these things. (And sadly, not everyone is aware.)

So, in real life, it's awkward. But let's get back to writing. In writing, it's also awkward. Remember how I probably wouldn't mention a person's race out loud except in specific situations? Well, in writing, you have to mention it explicitly or else the reader won't know. The reader cannot visualize the character unless you describe them. And the writer has to remember that they're writing in the face of long-held assumptions. It's likely, if the reader is American, that they will assume the character is white unless told otherwise. So if the writer wants the reader to get the fact that the character is not white, they may have to be a bit heavy-handed.

I hope that readers who do get it will not feel that they're being hit over the head or assumed to be stupid. I hope they will recognize that we live in a complicated world where not everyone does get it. And I hope that someday our world changes, and a person's race or other markers of difference are no longer classified as issues.

Until then, I'm okay with a bit of awkward description.