On Bisexual Characters and YA Literature

Originally posted at Diversity in YA

In response to my posts on Diversity in 2012 YA Bestsellers, bisexual-books asked:

Malinda, could you please expand/clarify the following? I’m not sure what you are trying to get at here.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that Pretty Little Liars has made a very comfortable home for itself on those lists, because I’m often asked whether having LGBT main characters is a problem. I know that the B is not the same as the L, G or (especially) T, but still: I’m thrilled to see a bestselling series with a queer girl lead selling so well.

This is a complicated question with a complicated answer, and I’ve been mulling it over for some time because I want to make sure I answer this as well as I can.

Please note that I'm trying to write this both for a general audience who may not have detailed understanding of these issues, and for the specific audience that asked this question: the people who run Bisexual Books. So I am focusing primarily on bisexual issues here, even though I touch on other issues as well to provide context.

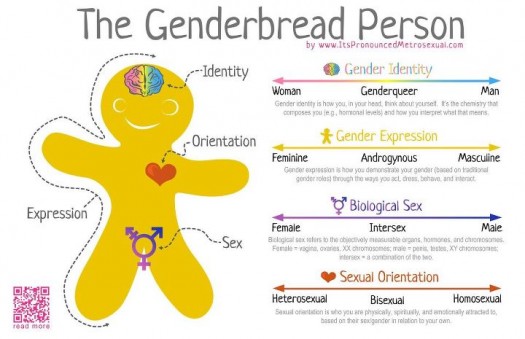

First, let’s think about the acronym LGBT. That stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender. Those are four different identities that have their own individual histories, issues, complications, and stereotypes. (I’ve decided not to delve into Q/queer here, because that’s a different discussion.) The primary thing I’m saying when I say “the B is not the same as the L, G, or (especially) T” is that each of those identities warrants separate consideration because they are separate identities. (I will address that word “especially” later on in this post.)

Yes, lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people do encounter some of the same issues, partly because they are grouped together under that LGBT acronym. All folks within the LGBT acronym can face homophobia, even if it’s not accurate homophobia. That is, a transgender person could face homophobic discrimination even if they are not gay. And it’s useful for LGBT people to band together to fight certain kinds of discrimination, such as the movement for marriage equality.

However, the LGBT acronym also has the unfortunate side effect of blurring together distinct identities and of erasing some identities. I can’t tell you how often representation of or discussion of “LGBT” people in the media is actually about gay men only. Oh wait, I wrote a blog post about it back in May 2012: Queer women and (in)visiblity, in which I discussed an NPR piece I heard about the impact of television on public opinions about gay people. That NPR piece basically dismissed and then proceeded to ignore the incredibly significant work that lesbians and bisexual women have done for LGBT representation.

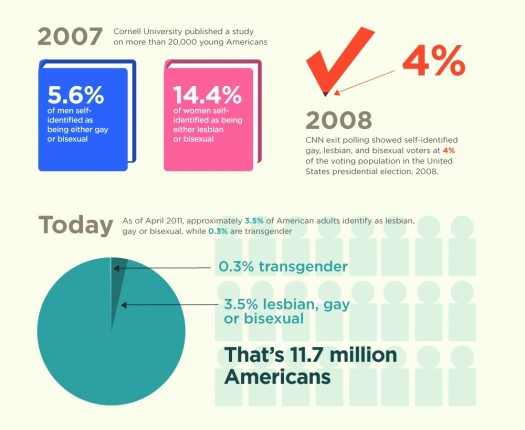

Relatedly, when I did my analysis of statistics on LGBT young adult books published in the U.S. from 1969 to 2011, I determined that 50% of those titles were about cisgender boys, with only 25% focusing on cisgender girls, and only 4% on transgender characters. That post, despite its flaws (which I still, at some point, hope to remedy), is probably my most widely linked-to post. It still gets hits from random places on the internet today, one and a half years later. The big takeaway from that post, though, was my conclusion that less than 1% of YA novels have LGBT characters.

Hidden in that conclusion is this fact: less than half of one percent of YA novels have lesbian/bisexual female characters, and even less than that have transgender characters.

"LGBT" is a problematic term because it erases those distinctions. I understand why the term exists, but I often find myself extremely frustrated with it, because the experiences of L, G, B, and T people can be so different. Within the “LGBT community,” I’ve rarely seen extensive social mixing across the letters of that acronym. That could be because I’m in San Francisco, and there are so many of us that it’s a lot easier to divide into niche groups here than it would be in a small town where the LGBT folks stick together because there simply aren’t that many of them.

But the fact remains that the needs and experiences of the lesbian community often differ significantly from the needs and experiences of the gay male community. Sexism alone makes the lesbian and gay male experiences vastly different.

Additionally, transgender people have been misunderstood and stereotyped to a degree that is rarely addressed in the mainstream discourse on LGBT people. When I said “especially” in regard to the T part of LGBT, I meant that trans people face particular and difficult challenges in fair and accurate representation, though I do believe things are moving in a positive direction. This is due to longstanding and entrenched transphobia throughout society, but also because the trans rights movement hasn’t been active as long as the gay rights movement. Even though T is part of LGBT, that doesn’t mean their stories are being told; the T is often silenced.

When it comes to bisexuals, there are a whole lot of issues around biphobia that are not faced by lesbians, gay men, or non-bisexual trans folk. There are so many awful stereotypes about bisexuals as promiscuous, deceptive, or just plain confused. Sometimes the very existence of bisexuals is challenged by lesbians or gay men (“bisexual is just one step on the way to gay”). Sometimes queer folks feel threatened by bisexuals because they fear their bisexual lovers will leave them for a straight relationship. And then there’s the extreme sexualization of bisexual women on the part of so much mainstream heteronormative media. All of these stereotypes are messed up, and they are distinct to bisexuals.

Finally, I think there may be a perception floating around our culture that bisexuals are sort of a watered-down version of gay, and this is a big problem. This perception enables mainstream cultural creators to think: Oh, I should have some LGBT representation, let’s stick in a bisexual girl (this would never happen with a bisexual boy, because of a host of issues around homophobia). Then that bisexual female character can have a fling with another girl to attract attention/check the “diversity” box, but meanwhile she can mostly be involved in a relationship with a man, so she largely appears straight. (This has been the story line of so many TV shows involving “bisexual” characters over the decades.)

In case it’s not clear, I want to underscore the fact that I think this is wrong. This kind of representation of “bisexual” women essentially erases the existence of people who are bisexual. It’s flat, two-dimensional, bad storytelling based on stereotypes that primarily serves to underscore even more stereotypes.

Luckily, I think this is slowly but surely changing. Recently on TV, we’ve seen some much more complicated and nuanced representations of bisexual characters, for example on Pretty Little Liars (based on that bestelling book series) and Lost Girl (one of my favorite shows).

In terms of YA, representations of bisexual characters remain few and far between. (I do recommend Sara Ryan’s Empress of the World, Laura Goode's Sister Mischief, and Nina LaCour's The Disenchantments for a variety of representations of female bisexuality. The only representation of male bisexuality I can think of in a YA novel is Cassandra Clare's series that includes secondary character Magnus Bane.) I tried to think through possible technical reasons for the lack of bisexual characters, perhaps because of YA’s focus on specific ages and narratives, and maybe those reasons do exist, but honestly…I think the lack is probably due to heteronormativity combined with biphobia. Bisexuality challenges the hetero/homo binary, and a lot of people (on both sides of the binary) are uncomfortable with that.

Personally, I believe that sexuality can be fluid, and very little is final when one is seventeen (although it may seem that way at the time). I even wrote my novels Adaptation and Inheritance partially to be a metaphor on bisexuality. Even more personally, I used to identify as bisexual myself. (I identify as a lesbian now, but call me whatever you like.) So to be honest, when it comes to bisexual characters in YA, I have a horse in this race.

I love the fact that Pretty Little Liars, one of the biggest bestselling YA series of 2012, has a bisexual main character in it. The series’ popularity is certainly significant. It means that YA readers are more than ready for bisexual characters; they already know and love them. I hope the publishing industry notices that.