Diversity in ALA's Best Fiction for Young Adults

Originally published at Diversity in YA

Every January, the Young Adult Library Services Association, a division of the American Library Association, releases the Best Fiction for Young Adults list. This list includes novels, short story collections, and novels in verse that were published in the past 16 months. These titles, according to YALSA, “are recommended reading for ages 12 to 18.”

As librarian and blogger Kelly Jensen explained to me, “I think the BFYA is useful for librarians who don’t know YA lit well, who may be the only librarians in their library or system, or who have been tossed into teen librarianship without the background that would help them in building a collection. I think people use BFYA as a collection building tool, which has a lot of merit to it.”

Thus, because the BFYA lists are used for collection development — and because the adjective “best” indicates that these titles are of high quality — being included on a BFYA list can help both sales and book buzz. (Full disclosure: My novel Huntress, published by Little, Brown, was on the 2012 BFYA list.) Indeed, the ALA’s various lists and awards can be extremely significant in terms of a YA book’s overall success — and thus, the author’s literary career.

The BFYA lists are typically fairly long, including approximately 100 titles, which suggests that there’s room for plenty of diversity. The question is: How much diversity is included in the BFYA lists? That is what I set out to discover.

Methods

Before 2011, the Best Fiction for Young Adults list was known as the Best Books for Young Adults (BBYA) and included both fiction and nonfiction. In order to limit the sample under analysis while also providing some range, I decided to focus on BFYA only: three lists from 2011, 2012, and 2013.

I decided to look for a few particular things:

The percentage of authors of color on the lists.

The percentage of main characters of color on the lists.

The percentage of LGBTQ main characters on the lists.

The percentage of disabled main characters on the lists.

In order to make every effort to check all the data thoroughly, I invited several people to assist me in combing through the lists. Elizabeth Burns,Hannah Gomez, Kelly Jensen, Lalitha Nataraj, and Cindy Pon all helped examine the lists for diversity, and without their assistance I’m sure I would have missed many things. Nonetheless, any mistakes presented in the final data here are my own.

A list of all BFYA titles used in this analysis (titles with characters of color, LGBT characters, or characters with disabilities) is available here on Google Documents.

Authors of Color

The representation of authors of color among the hundreds of authors included on the BFYA lists from 2011 to 2013 is regrettably poor.

Chart indicating percentage of authors of color compared with white authors in the Best Fiction for Young Adults lists, 2011-13. 2011: 6.9% authors of color; 2012: 12.4% authors of color; 2013: 7.8% authors of color.

According to Lee & Low, a multicultural children’s publisher, 37% of the US population in 2012 was comprised of people of color. That doesn’t mean that 37% of a list that comprises the “best fiction for young adults” must be written by authors of color, but when the percentage of authors of color ranges from 6.9% to 12.4%, that does present quite a gap.

Additionally, it was interesting to note that 24 of the 29 authors of color on the list wrote books that had main characters of color. Only five of those 29 authors’ books have white main characters.

I should also note that there was one short story collection on the 2012 list, The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: Fourteen Amazing Authors Tell the Tales, that was edited by Chris Van Allsburg, a white writer, but which includes stories by three authors of color: Sherman Alexie, Walter Dean Myers, and Linda Sue Park. Because the primary author’s name on this book is Van Allsburg’s, I did not include the other authors in my count of authors of color, but I wanted to point it out.

Here are the authors of color who were included in the 2011, 2012, and 2013 BFYA lists:

Authors of color from ALA’s Best Fiction for Young Adults, 2011-2013: Randa Abdel-Fattah, Swati Avasthi, Kendare Blake, Coe Booth, Cara Chow, Michelle Cooper, Matt de la Pena, Maria Virginia Farinango, Christina Diaz Gonzalez, Hiromi Goto, Angela Johnson, Dream Jordan, Julie Kagawa, Y.S. Lee, Malinda Lo, Marie Lu, Kekla Magoon, Guadalupe Garcia McCall, Walter Dean Myers, Vaunda Micheaux Nelson, Nnedi Okorafor, Anna Perera, Mitali Perkins, Benjamin Alire Saenz, Francisco X. Stork, Padma Venkatramen, Jacqueline Woodson, Lisa Yee

Characters of Color

The representation of characters of color among the BFYA lists was much better, because white authors also write about characters of color. In the charts below, the percentage of characters of color are shown in relation to white characters. If a book had multiple main points of view, such as Marie Lu’s Legend, which is written from alternating points of view from two main characters, I counted both characters. Therefore, the number of characters is higher than the number of books on the BFYA lists.

While recognizing that all categorizations of race and ethnicity are imperfect, I broke down race/ethnicity as follows:

White - Characters with European origins (This definition is different from the US Census definition, which also includes those from the Middle East and Northern Africa, because I wanted to count Middle Eastern characters)

Asian - Characters with Asian origins including members of the Asian diaspora and South Asians

Black - Characters with African origins including African Americans

Latino - Hispanic and Latino Americans; characters from Latin America (Exception: Indigenous people are identified as Indigenous even if they’re from Latin America)

Mixed Race - Characters of mixed race backgrounds

Indigenous - Including American Indians and Indigenous peoples from around the world

Middle Eastern - Characters from the Middle East, e.g., Iran

SF/F of color - Characters from a secondary or futuristic science fiction or fantasy world who have a race that does not precisely match our contemporary US understandings, but which is situated as being nonwhite in that secondary or futuristic world

Unspecified of color - See details with each chart

Chart showing percentage of characters of color in 2011 BFYA list. Overall: 16.8% characters of color, 88.2% white characters. Specifically: 4.0% Asian, 3.0% Black, 3.0% Latino, 2.0% Mixed Race, 2.0% Indigenous, 1.0% Middle Eastern, 1.0% SF/F of color, 1.0% Unspecified of color.

Only one title on the 2011 list had a character that was “unspecified of color”: Trash by Andy Mulligan, which is set in an unnamed third world country; the author has deliberately chosen to not state the characters’ race.

11 of 17 titles with main characters of color on the 2011 list were written by white authors.

Chart showing percentage of characters of color in 2012 BFYA list. Overall: 21.2% characters of color, 78.8% white characters. Specifically: 3.4% Asian, 5.1% Black, 1.7% Latino, 5.1% Mixed Race, 1.7% Indigenous, 1.7% Middle Eastern, 1.7% SF/F of color, 0.8% Unspecified of color.

On the 2012 list, I designated Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens as “unspecified of color” because the title does not have a main character; it has a cast of approximately nine characters. Two are of color; three are LGBTQ; and one is Deaf. For that reason, Beauty Queens will appear on the charts for LGBTQ and Disabled characters also.

13 of 25 titles with main characters of color on the 2012 list were written by white authors. One title, Queen of Water, was co-written by a white author, Laura Resau, and an Indigenous author, Maria Virginia Farinango.

Chart showing percentage of characters of color in 2013 BFYA list. Overall: 21.9% characters of color, 78.3% white characters. Specifically: 2.8% Asian, 9.4% Black, 0.9% Latino, 5.7% Mixed Race, 2.8% SF/F of color.

The 2013 list did not include any Indigenous or Middle Eastern main characters.

15 of 23 titles with main characters of color on the 2013 list were written by white authors.

According to Lee and Low’s analysis of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s statistics, approximately 10% of all children’s books published every year contain multicultural content. The BFYA lists are not directly comparable to these statistics because the CCBC statistics cover all children’s books, not only YA, but it’s still interesting to see that the BFYA lists have a higher percentage of books with characters of color than children’s books overall.

LGBTQ Characters

The proportion of LGBTQ characters on the BFYA lists was complicated by the fact that there were a couple of books that destabilized gender but did not include an overtly LGBTQ main character (Every Day by David Levithan, Brooklyn Burning by Steve Brezenoff). Additionally, a few books were focused on LGBTQ issues (including hate crimes or dealing with another character’s sexual orientation) but were not about an LGBTQ main character. Here’s how the BFYA lists broke down according to these various ways of understanding “LGBTQ”:

Chart showing percentage of books with LGBTQ characters or issues in BFYA, 2011-13. 2011: 2%, with 2 books with LGBTQ main characters. 2012: 3.4%, with 3 books with LGBTQ main characters, 1 book with gender-destabilizing narrative, and 1 book with LGBTQ as issue. 2013: 4.9%, with 5 books with LGBTQ main characters, 1 book with gender-destabilizing narrative, and 3 books with LGBTQ as issue.

In 2012 I counted the number of YA books about LGBTQ characters that were published overall. According to that data, 1.6% of YA books published in 2012 included LGBTQ main characters.

The 2013 BFYA list incorporates books published in 2012. From the 2013 BFYA list, 5 out of 102 books included LGBTQ main characters, which is 4.9% of the list. Even though this is only 5 titles, that’s still about three times higher than the overall proportion of LGBTQ YA, and the number of LGBTQ books on the BFYA has been rising. I’m going to count that as a win.

Characters With Disabilities

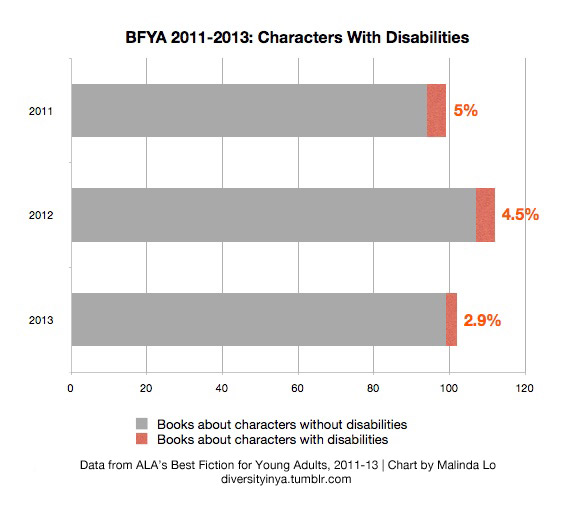

According to the US Census, approximately 5.2 percent of school-aged children (aged 5 to 17) in the US were reported to have a disability in 2010. Although 5% of the titles on the 2011 BFYA list included main characters with disabilities, by 2013 that percentage had fallen to 2.9%.

Chart showing percentage of characters with disabilities in BFYA, 2011-13. 2011: 5%. 2012: 4.5%. 2013: 2.9%.

The disabilites represented in these titles are:

Asperger’s Syndrome

Deaf characters

Blind characters

Characters dealing with cancer-related disabilities

Characters with a learning disability

Characters with obsessive-compulsive disorder

Characters who are amputees

Characters with MSRA-related disabilities

Some Conclusions, More Questions

The ALA’s Best Fiction for Young Adults lists are voted on by a committee of librarians who read YA books throughout the year. At ALA’s annual Midwinter Meeting, feedback from teen readers is invited, and that feedback is considered in addition to the librarians’ own opinions. Later this week, we’ll have an interview with Edith Campbell, one of this year’s BFYA committee members, who will explain a bit more about what the committee does. You can read more about the BFYA’s policies here.

As with every awards list, the results are shaped by personal tastes. Diversity is not a stated goal of the BFYA list, and there are other lists that the ALA produces that focus on specific kinds of diversity (e.g., the Rainbow List for LGBTQ books. According to the BFYA’s Committee Function Statement, BFYA is:

“…a general list of fiction titles selected for their demonstrable or probable appeal to the personal reading tastes of the young adult. Such titles should incorporate acceptable literary quality and effectiveness of presentation.”

The question is: Who is this “young adult” reader that this list is supposed to appeal to? Considering race alone, in a US where 37% of the population is people of color, and where “half of all children under 18 are expected to be non-white in five years” (MSNBC), should the BFYA lists attempt to diversify? How does quality — that slippery concept of “best” — relate to race and representation? These questions are further complicated when you bring in sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability.

And what about authors of color? What can be done to increase representation in that arena, both in general and in lists and awards that seek to recognize the best of YA? Is that important? Should it be?

Obviously, BFYA is only one aspect of the very complex publishing industry, which is only one part of the even bigger and more complicated real world. Race and representation are thorny subjects that cannot be fixed in simple ways. My hope is that presenting this data will help shine a light into one corner of this discussion, if only by revealing what is already there.