Racism and the Chinese American Experience

Notes From the Telegraph Club #4

This is the fourth installment in my series Notes From the Telegraph Club, which dives into the research I did to write my most recent novel, Last Night at the Telegraph Club. I do my best to avoid major spoilers, but I do mention some things that happen in the book in order to explore the historical context. I don’t believe that knowing some plot points will spoil this book, but if you’d like to avoid all potential spoilers, you may wish to read the book before reading these essays.

A major part of the background research for Last Night at the Telegraph Club involved learning how Lily’s Chinese American identity would have been experienced by her and how it would have been perceived by others—not only her family and community, but by whites and other non-Chinese. My goal when researching the Chinese American experience was not to use every detail in the text, but to fill my mind and subconscious with a multilayered knowledge of what it might have been like to be Lily. Some of that historical research emerged on the page in specific interactions or language, but more of it was expressed through Lily’s engagement with the world. For example: the way she reacts to being catcalled by a white man on the street, or the tension she feels when she prepares to bring a white friend into Chinatown.

In this essay, I’m expanding on the Author’s Note I wrote for Last Night at the Telegraph Club and focusing specifically on racism and the Chinese American experience. I’m sure that a lot of this history is unfamiliar to most readers because Chinese American history is not widely taught in American schools. But even Chinese Americans may be unfamiliar with much of it because we have grown up learning to brush off racist incidents, and to be silent about the way we are often treated by non-Chinese, and especially whites.

I admit I wasn’t originally going to include an essay on this in my Notes From the Telegraph Club series, because it’s actually quite traumatic to research and write about these issues. But given the recent, tragic shooting of six Asian women in Atlanta, and the sudden, mainstream attention to anti-Asian racism, I felt that sharing this history with my readers was the least I could do. Please be aware that this essay contains disturbing descriptions of violent anti-Chinese racism.

Note: This essay focuses on the Chinese American experience. Asian Americans of all ethnic backgrounds have faced anti-Asian racism, and often have been mistaken for each other during racist incidents. For more on the history of Asian Americans, I recommend this PBS documentary series.

The Chinese Must Go

The first Chinese landed in San Francisco in 1848, and soon afterward settled in the center of the city near Portsmouth Square in an area that would become known as Chinatown. For the next several decades, anti-Chinese bigotry tangled with demand for Chinese labor. White American entrepreneurs needed Chinese workers to build railroads and wash laundry, but white American workers resented the Chinese for taking those jobs.

This anti-Chinese sentiment was expressed in numerous ways, from advertisements to popular songs to political cartoons.

In San Francisco, local ordinances targeted Chinese without naming them by selectively enforcing housing laws, forcing all jailed men who couldn’t pay their fines to shave their heads, and making it illegal to carry a pole with baskets hanging off the ends (this was how Chinese laundry workers carried laundry).

In 1870, Congress prevented Chinese Americans from voting by specifically denying Asians the right to naturalization. In 1875, the Page Act barred the immigration of Chinese women, who were believed to be prostitutes. And in 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration ban in the United States targeting a specific ethnic group. It remained in place until World War II.

Anti-Chinese sentiment was not limited to laws; it was also expressed violently.

In 1871, up to two dozen Chinese men were shot and lynched by a mob in Los Angeles in what became known as the Chinese Massacre.

In 1877, five Chinese farm workers were murdered by a group of armed white men in Chico, California. They were acting under orders from the Workingmen’s Party, which was led by the demagogue Denis Kearney, who was known for his slogan, “the Chinese must go.”

Also in 1877, San Francisco’s Chinatown was burned and looted by an angry mob of thousands, and Chinese were shot in the streets. This riot led to an intervention from National Guard and the U.S. Navy, and resulted in the death of four people.

In 1885, 28 Chinese miners were killed by white miners, who also looted and burned the Chinese settlement in Rock Springs, Wyoming, in what became known as the Rock Springs Massacre.

In 1887, 34 Chinese gold miners were murdered and robbed in Hells Canyon, Oregon, by a gang of white ranchers, in what became known as the Snake River Massacre.

Despite these violent acts, Chinese immigrants continued to fight for their rights through the court system, taking some cases all the way to the Supreme Court. Although the Supreme Court often sided with anti-Chinese racists, in 1898 Chinese Americans scored a hard-won victory. In United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court ruled that all people born in the U.S. became citizens by birth, including Chinese immigrants.

No Better Than Beasts

The dawn of the twentieth century brought continued strife for Chinese immigrants in America. In 1899, when a few people died of plague in Hong Kong, Chinese were forbidden from immigrating to the U.S., and San Francisco’s Chinatown was quarantined and nearly razed by xenophobic city officials.

In 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended indefinitely. In 1905, the Supreme Court ruled that Chinese immigrants, even those who were American citizens by birth, could no longer appeal immigration decisions in court.

And then, on April 18, 1906, a massive earthquake struck San Francisco. Chinatown, like much of the city, burned. It was also looted by wealthy San Franciscans and members of the military while Chinese residents were denied access to their own homes. But the earthquake also destroyed thousands of public documents, which gave immigrants the opportunity to claim they were born in America, and therefore were U.S. citizens. These immigrants became known as “paper sons.”

American immigration authorities were suspicious of these claims, which led to lengthy investigations. In 1910, the U.S. government established the Angel Island immigration facility, where Chinese were imprisoned—sometimes for months or years—while they were investigated. Conditions at Angel Island were extremely poor. One Chinese man, L.D. Cio, later described it as “a prison with scarcely any supply of air or light. Miserably crowded together and poorly fed, the unfortunate victims are treated by the jailers no better than beasts.”

In June 1914, a group of Chinese Americans sent a petition to President Woodrow Wilson, writing:

“We helped build your railroads, open your mines, cultivated the waste places, and assisted in making California the great State she is now. In return for all this what do we receive? Abuse, humiliation and imprisonment. We ask that these things be changed, and that we be treated as human beings instead of outlaws.”

But change was slow, scattered, and hard-fought.

In the 1920s, San Francisco’s Oriental School, which educated Chinatown children in a “separate but equal” system that would not be officially abolished until 1954, was renamed the Commodore Stockton School. In 1925, Francisco High School in North Beach was ordered to take in Commodore Stockton students, and although some white families objected, they were overruled. For the first time, Chinese students in San Francisco were allowed to go to an unsegregated school.

At the same time, Anna May Wong began to build a career for herself in Hollywood, starring in classic films including Shanghai Express (1932) with Marlene Dietrich. But despite being the most famous Chinese American actress of the time, she was denied the lead role in the major film adaptation of Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth (1937), which was instead given to a white woman, Luise Rainer. In fact, most of the film’s cast consisted of white actors in yellowface makeup; Chinese American actors were only cast in minor roles.

The Rise of the New China

Time magazine, March 1, 1943

The generally favorable portrait of China in The Good Earth was partly due to the intervention of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Republic of China. His wife, Soong May-ling, aka Madame Chiang-Kai-shek, was a Wellesley College–educated woman who spoke English fluently and was so adored by the American media that she appeared on the cover of Time magazine three times.

In 1943, she embarked on a national tour to raise money and goodwill for China and became the first woman to address a joint session of Congress. Upon her arrival in San Francisco, the Chronicle gushed: “The talented, courageous and dainty first lady of China—Madame Chiang Kai-shek—has a background of ancestry and accomplishments as fascinating as the rise of the new China.”

After Madame Chiang’s tour, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in December 1943 and established a quota that permitted 105 Chinese to immigrate each year.

This slight expansion of immigration opportunity for Chinese Americans, and the more favorable view of China in America, was due in no small part to Japan’s aggression during World War II. As Japan became the enemy, China became an ally. In the United States, Japanese Americans were incarcerated during the war, while many Chinese Americans carried cards that declared they were Chinese, not Japanese.

World War II also provided an additional route to U.S. citizenship for Chinese immigrants: the military. When the United States entered the war after Pearl Harbor, approximately one-third of all Chinese American men between ages fifteen and sixty enlisted, in comparison with about 11 percent of the general population. Military service is not traditionally valued in Chinese culture, but perhaps one reason so many Chinese American men enlisted was because it enabled them to become naturalized American citizens, regardless of their previous immigration history.

This is the choice that Lily’s father, Joseph Hu, makes. He first comes to the U.S. to attend medical school in San Francisco in 1932, where he meets and falls in love with Grace, who becomes Lily’s mother. Joseph represents a category of Chinese immigrant rarely depicted in popular culture and is inspired by my own family’s experience.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, sons (and a few daughters) from upper class families in China sometimes came to the United States to study at American universities. These Chinese students were not subject to the same immigration restrictions as laborers because of their class privilege, and they generally returned to China after completing their education. Some of them came from wealthy families; others were funded by scholarships. Many of them learned English in missionary schools in China. Although these students faced racism like all Chinese immigrants, their privileges smoothed their passage to America.

Because Chinese Exclusion was still in place when Joseph married Grace in 1936, he could not become an American citizen through marriage. But I believe that had China not been invaded by Japan in 1937, he would simply have taken Grace back to his homeland. However, Japan did invade China, and then it attacked the U.S. at Pearl Harbor, prompting the U.S. to enter World War II. Military enlistment then became the only way that Joseph could legally keep his family together.

After the war, quotas for Chinese immigrants loosened, first allowing Chinese American veterans to bring their wives to the United States, then extending that right to non-veteran Chinese Americans. Additionally, thousands of Chinese students came to America in search of a modern education that they could use to rebuild their devastated homeland.

Lily’s Aunt Judy was one of these students, and once again, geopolitics intervened in her plans. When Mao Zedong’s Communist Party gained control of China in 1949, Chinese students like Judy were stranded in the U.S., which did not recognize the Communist government until 1972. Many Chinese students were able to be naturalized, especially after the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952, but the coast was not clear for Chinese immigrants.

Due to the anti-communist fervor that gripped the country during the 1950s, Chinese immigrants were harassed by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and some were deported to the People’s Republic of China, notably Dr. Hsue-shen Tsien, one of the co-founders of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory where Judy works as a computer.

Lily’s Chinatown

The vast majority of Chinese immigrants who came to America in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were from southern China. Robbed of the ability to form stable families due to the Page Act, these men formed a bachelor society in the urban Chinatowns where they lived. They organized mutual-aid groups based on their home villages or family surnames. Businessmen founded the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, or the Chinese Six Companies, to officially represent their interests and Chinatown.

By the early 1950s, San Francisco’s Chinatown had developed two distinct but overlapping populations: the aging group of bachelors who’d immigrated before the war, and a growing community of families based in the merchant class. Lily’s friend Shirley is rooted in this part of Chinatown, and her aspirations to compete in the Miss Chinatown pageant echo the broader goals of Chinatown’s business community.

Lily and Shirley’s generation was much more Americanized than their parents. They went to integrated schools and were influenced by popular culture just like white kids. In Growing Up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Irene Dea Collier recalls:

“We had in the 1950s Chinese American teenagers becoming just American teenagers. In Chinatown we had Topps Fountain, we had the Chinese owned and operated soda fountain Fong-Fong. We had kids running around in purple jackets and slicked-back hair looking like Elvis Presley.”

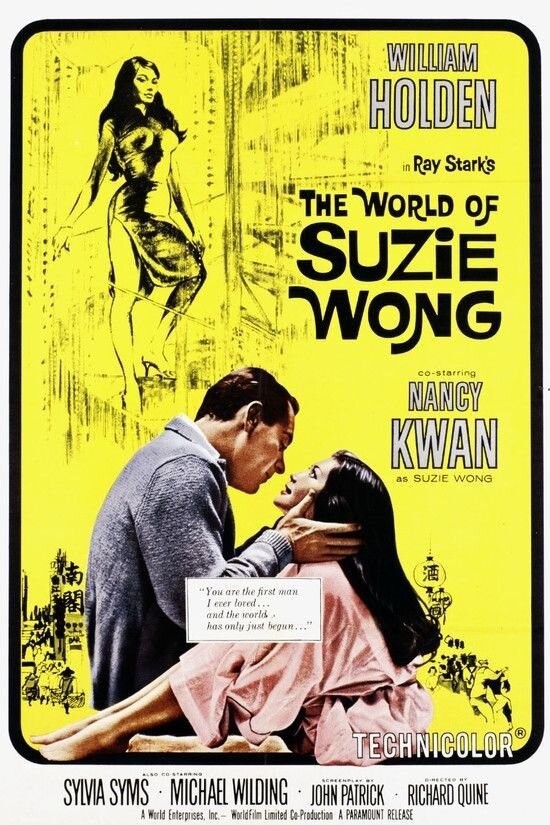

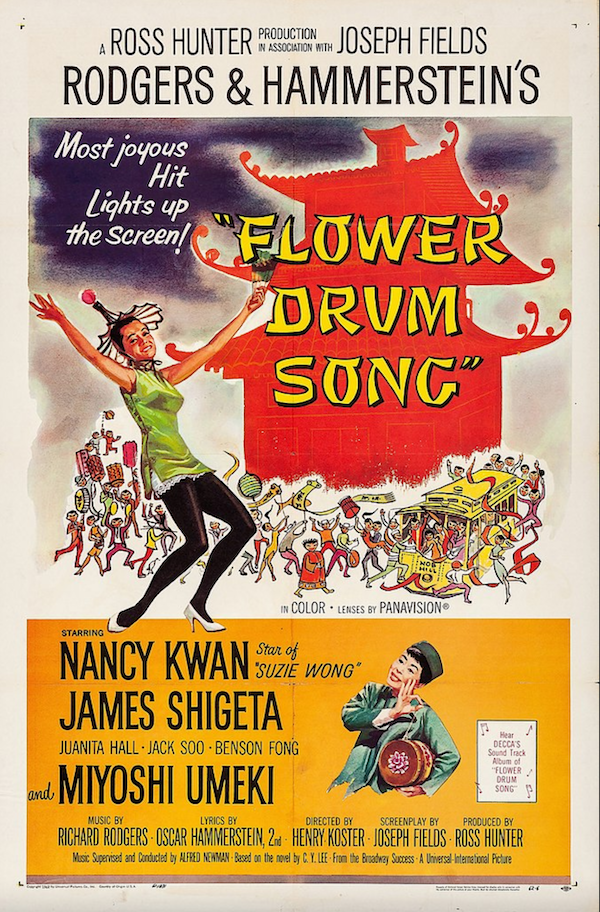

At the same time, Asian women, who had always been sexualized in the West, saw growing mainstream acceptance under certain parameters. Novels and their film adaptations such as Love Is a Many Splendored Thing, The World of Suzie Wong, and The Flower Drum Song became popular hits. According to historian Shirley Lim in A Feeling of Belonging, productions such as these, along with beauty pageants, became part of an “Oriental wave” that contributed to the mainstreaming of “a certain type of Asian femininity—foreign-born, slender, and coy yet sexual.”

And yet the Communist takeover of China in 1949, followed rapidly by Korean War in 1950 and the rise of McCarthyism, which peaked during the McCarthy hearings in 1954, led to an atmosphere of fear and paranoia within the Chinese community.

Franklin Woo, who was involved with the Chinese American Democratic Youth League (aka Min Ching or Man Ts’ing), in San Francisco in the 1950s, recalled in Longtime Californ’:

“We knew the FBI was keeping a close eye on us, and we even suspected there was an informer among us. ... The FBI people began coming to our homes, going to talk to our relatives, friends, where we worked. I guess when they got the Immigration Office working on us, though, we knew the Min Ching was coming to an end. I remember the immigration people would stop Min Ching members on the street and demand to see their papers, just to harass us. Once they discovered somebody had false papers, they would begin proceedings for deportation."

In 1956, the Immigration and Naturalization Service began the Chinese Confession Program, which promised forgiveness if an immigrant revealed their fraudulent “paper son” documents. However, if one confessed, that would implicate by extension their family, and sometimes the information revealed was used to deport suspected Communist sympathizers. In fact, the Confession Program snared members of the Man Ts’ing, and ultimately revoked the citizenship of at least two of its members.

When Lily meets several members of the Man Ts’ing in Last Night at the Telegraph Club, she is not aware of their political reputation, although she is certainly aware of the anti-communist fervor in America at the time. She lives through it at school during the duck-and-cover air raid drills, which are preparation for a potential Russian invasion. She remembers the very recent (to her) Korean War. She understands, when her parents warn her to stay away from the Man Ts’ing, that it’s serious.

However, these incidents are part of normal life for her, so I tried to embed them in the world of Last Night at the Telegraph Club as if they were to be expected. I didn’t want to whitewash reality, but nor did I want to make it seem more horrific than it would have been to the people living through it. For Lily and her Chinatown community, things are sometimes bad, but they’ve been much, much worse.

I grew up in a Chinese American family in the 1980s and 90s where I was vividly aware of the sacrifices my parents and grandparents had made to give me a good life. And yet, the American culture that surrounded me—on television and in school, at the movies and in public—did not acknowledge this. The disconnect between the culture of my family and the culture of the outside world was often disorienting to me. Although Lily grew up in a different time, I believe she also would have experienced this dichotomy—the one between insider and outsider—which is often confusing. Growing up, for Lily, involves connecting the dots between cause and effect, insider experience and outsider perception.

Last Night at the Telegraph Club ends in the mid-1950s, but I imagine that Lily would be drawing these connections for the rest of her life, just as I am.

Support My Writing

I’ve been blogging about books, popular culture, and writing since the early 2000s. If my writing makes your life more enjoyable or shows you a new perspective, please consider supporting my ability to write with a donation. Your support means the world to me.

References

Disclosure: Some links go to Bookshop.org, where I am an affiliate. If you click through and make a purchase, I will earn a commission.

Chang, Iris. 2003. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. New York: Viking.

Lim, Shirley Jennifer. 2006. A Feeling of Belonging: Asian American Women's Public Culture, 1930-1960. New York: New York University Press.

Nee, Victor G., and Brett de Bary. 1973. Longtime Californ’: A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown. New York: Pantheon Books.

Wong, Edmund S. 2018. Growing Up in San Francisco's Chinatown: Boomer Memories From Noodle Rolls to Apple Pie. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

View more posts in the Notes From the Telegraph Club series