The True Story of the Raid on Tommy’s Place

Notes From the Telegraph Club #7

This is the seventh installment in my series Notes From the Telegraph Club, which dives into the research I did to write my most recent novel, Last Night at the Telegraph Club. I do my best to avoid major spoilers, but I do mention some things that happen in the book in order to explore the historical context. I don’t believe that knowing some plot points will spoil this book, but if you’d like to avoid all potential spoilers, you may wish to read the book before reading these essays.

Grace Miller tending bar (Photo from the Grace Miller papers, San Francisco Public Library)

September 8, 1954, was a Wednesday—likely not the busiest day of the week at Tommy’s Place, a bar in San Francisco—but by nine p.m. more than two dozen patrons were either at the main bar, located at 529 Broadway, or downstairs at the connected 12 Adler Place, which opened onto Columbus Avenue.

Upstairs at Tommy’s, tables for two lined both walls, a 15-seat bar was built into the far corner, and framed pictures of women hung on the walls. At first glance, it looked like any other San Francisco bar, but if you looked closer, you’d realize there were more women than men in the establishment. If you went downstairs to 12 Adler Place, you’d notice the bartenders were also women, which was a rarity. At the time, women weren’t allowed to tend bar in San Francisco unless they were the owners, which meant 12 Adler and Tommy’s Place were owned by women.

And you’d probably notice the way the patrons looked. Some of the women wore dresses and skirts, which was the norm, but a good number were in slacks and blazers and had short, masculine haircuts. They were butches and femmes; in other words, lesbians. Tommy’s Place and 12 Adler were lesbian bars.

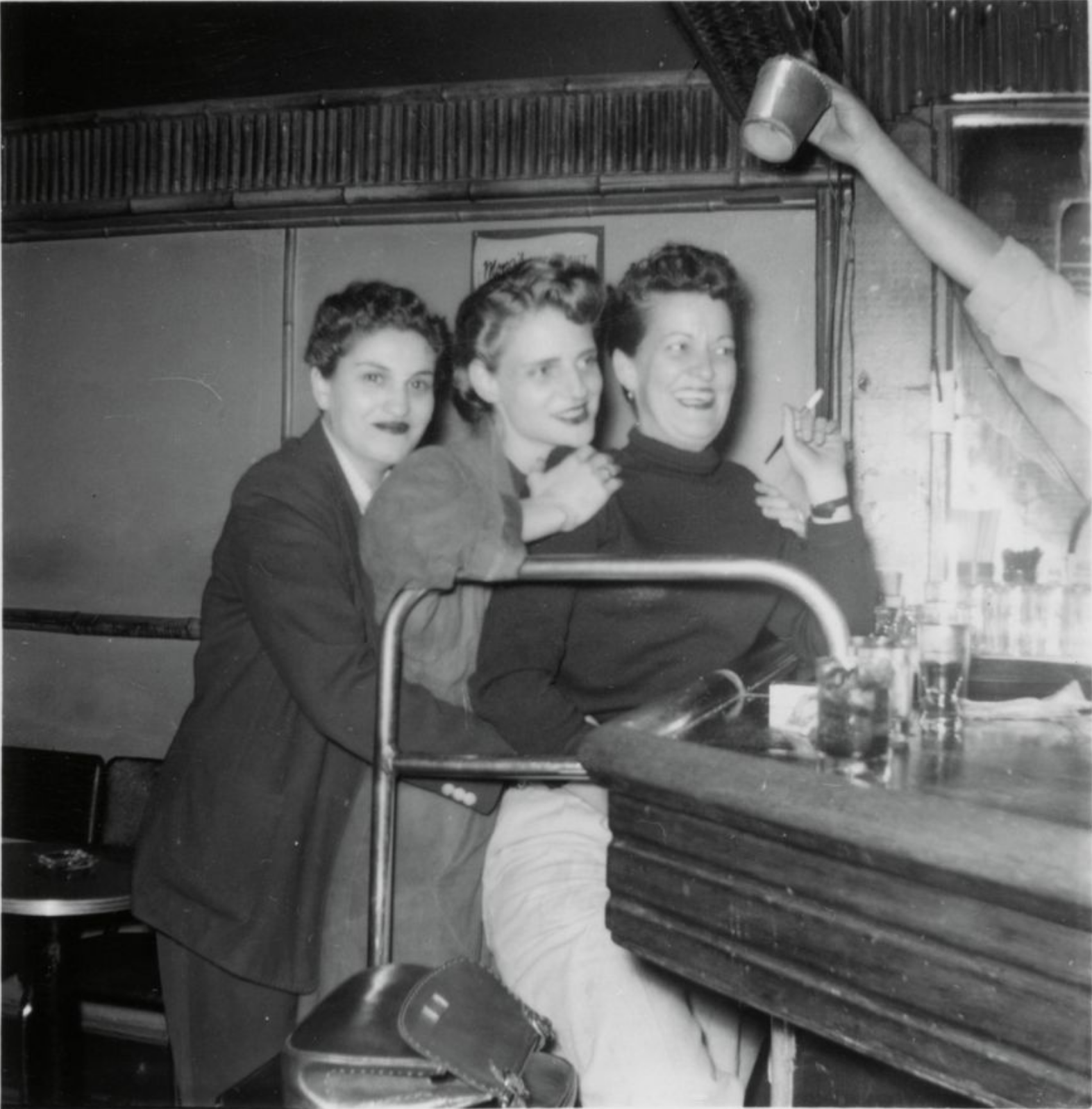

Grace Miller, Joyce Van de Veer, and possibly Jeanne Sullivan at bar (Credit: SAN FRANCISCO HISTORY CENTER, SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY)

The two connected bars had been opened in 1952 by openly lesbian Tommy Vasu, who had also previously run Tommy’s 299, which was San Francisco’s first lesbian-owned bar. Tommy’s 299 was open from 1948 until it was raided by the police and closed in early 1952. A few months later, Vasu opened Tommy’s Place and 12 Adler, but kept her name off the liquor license. Instead, the bars’ legal owners were Vasu’s girlfriend, Jeanne Sullivan; Grace Miller; and Joyce Van de Veer. Vasu was rumored to be involved in prostitution, possibly worked as a pimp, and her bars were probably dives, but that didn’t stop San Francisco’s lesbian community from frequenting them. For many lesbians, they were spaces to call their own.

That Wednesday night at nine p.m., what could have been a comfortable, casual weeknight with friends at the local bar abruptly changed. San Francisco police arrived bearing warrants for two of the bar’s owners—Miller and Van de Veer—who were charged with contributing to the delinquency of minors by serving them alcohol. The bar’s patrons were told to leave, which they probably did as quickly as possible, plunging into the night and hurrying away from the neon-lit intersection of Broadway and Columbus.

Meanwhile, the police conducted a search of the premises and claimed to find a heroin kit hidden in the restroom at 12 Adler. Miller and Van de Veer were arrested, and the next day San Francisco’s newspapers printed photos of the two being charged, along with their home addresses. In the San Francisco Examiner image, both women have short hair and wear blazers, and though they must have been afraid, they look nonchalant, even a little annoyed that their night had been interrupted.

Their arrests and the raid on the bar resulted from a five-month-long police investigation, and while the raid itself was widely and sensationally reported in the local news, the drama would not reach its climax for months, until a December liquor license hearing. The raid would become part of an increasingly aggressive campaign by the police, city, and state governments against gay bars and gay people that would set the stage for the rise of the modern-day LGBTQ rights movement in the late 1960s.

Policing Homosexuality

Five months earlier, in March 1954, two teen girls, aged 14 and 16, were found in a Haight Street room “suffering from narcotic poisoning,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Their parents reported their daughters’ drug use to the police, who launched a lengthy investigation that involved interviewing a dozen other teen girls. Ultimately the drugs were traced back to Tommy’s Place and Jesse Winston, a 51-year-old Black man, who was arrested for dealing on September 1, 1954. A week later, Tommy’s Place was raided.

In 1954, San Francisco was in a briefly tolerant period for gay bars, and in the early 1950s many had proliferated in the North Beach district. Things had been different only a few years earlier, and they were about to change again.

The policing of gay bars in San Francisco began in earnest in the 1940s during World War II, as the military attempted to crack down on so-called “vice” in American cities, especially port towns, in order to regulate their personnel. In San Francisco, three agencies were involved in the policing of gay establishments: the police, the U.S. military, and the California Board of Equalization, which controlled liquor licenses. In Wide Open Town, historian Nan Alamilla Boyd explains: “By 1945, the local police, the military police, and the liquor board had developed a system to regulate and control queer public space.” Warnings issued by the police could lead to a bar being publicly listed as off-limits to military personnel, to arrests of any military personnel who visited them, to a suspension of the bar’s liquor license, and ultimately to police raids.

By 1951, all of the bars deemed off-limits to the military were believed to be gay bars, including all three lesbian bars that existed at the time: Mona’s, the Chi-Chi Club, and Tommy’s 299. In 1953, Tommy’s Place was also added to the off-limits list.

Interior of Tommy’s Place at 529 Broadway in 1954. Photo appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle on Sept. 10, 1954 and was republished in the Citywide Historic Context Statement for LGBTQ History in San Francisco by Donna J. Graves and Shayne E. Watson (2016).

During this crackdown against gay bars, in 1949 the Black Cat Restaurant, owned by Sol M. Stoumen, lost its liquor license for serving homosexuals. Stoumen sued, and his case eventually made it to the California Supreme Court, where he won. In 1951, the Stoumen v. Reilly decision legalized the public assembly of homosexuals in California. This meant gay people had the right to gather in a bar, and it led to a brief period, from 1951-55, in which gay bars flourished in San Francisco.

However, cultural norms around homosexuality had not changed. Homosexuality was still considered a psychological illness at best, and beliefs that we would characterize today as homophobic and transphobic were the norm. In 1954, the San Francisco police began a series of raids to crack down on what the press called “sex deviates.”

A front-page article in the San Francisco Examiner, published on June 28, 1954, recounted a raid on a gay bar that resulted in the arrests of 13 men “for a variety of charges arising from lewd and indecent conduct”:

Sex deviates were under stern warning yesterday that San Francisco will not tolerate their offensive conduct and will not allow itself to become a haven for homosexuals. The warning was backed up with a sweeping series of weekend raids on the known gathering places and a promise that police will continue to keep the pressure on to stem what Chief Michael Gaffey described as a marked recent influx of homosexuals.

An accompanying editorial titled “Needed: A Cleanup,” declared:

[T]here must be sustained action by the police and the district attorney to stop the influx of homosexuals. Too many taverns cater to them openly. Only police action can drive them out of the city.

But without cooperation from the courts or the liquor board, which were constrained at the time by Stoumen, the police couldn’t do much to shut down gay bars. That would change in 1955, and in the ramp-up to that change, the police investigated and eventually raided Tommy’s Place.

A “Vice Academy” for Teen Girls

Shortly after the raid, San Francisco’s newspapers splashed the story across their front pages with salacious headlines. The San Francisco Chronicle headline spanned the entire width of page one, shouting: “S. F. TEEN-AGE GIRLS TELL OF ‘VICE ACADEMY.’” In the San Francisco Examiner article, headlined “Bar Facing Ban In Dope, Sex Ring for Minor Girls,” Officer Russ Woods of the police juvenile bureau revealed what had been uncovered during the five-month investigation:

San Francisco Examiner (Sept. 10, 1954) article with a photo of Van de Veer (left) and Miller being booked after the raid

The girls admitted frequenting a “gay” bar—one catering to sexual deviates. Some of the girls recruited others from among their school classmates. It started as a lark. Then some of the girls began wearing mannish clothing. They called themselves “Butches.” Others, becoming sexual deviates, were the female counterparts and called themselves “Femmes.”

At Tommy’s Place, the girls bought benzedrine pills, a.k.a. “bennies,” a stimulant, as well as marijuana cigarettes and alcoholic drinks, despite being underage. One girl told the police that at closing time, someone (“either a man or a mannish woman”) would invite them to an after-party at Jesse Winston’s flat at 1225 Kearny Street on Telegraph Hill. The Chronicle spent several paragraphs describing Winston’s home with details that would be at home in a pulp novel:

Winston’s flat is a three-room affair. Its walls are freely decorated with nude and seminude calendar art, and there is also an admixture of pseudo-Chinese paintings and bric-a-brac. … Charles Morgan, Winston’s attorney, said his client lived there alone, but there were women’s as well as men’s clothes in the bedroom. Snapshots of a number of different girls were scattered through the apartment, and the Craig Rice mystery, “Having a Wonderful Crime,” lay open on one of the couches when the place was inspected yesterday.

One girl recounted being “recruited” to attend a party at Winston’s flat with about nine other women, whom she recognized from Tommy’s. The girls danced with each other, and Winston pulled the shades, locked the door, and served them vodka with orange juice. Later, he brought out some pot, and some of the girls rolled joints and smoked them.

According to Inspector Ethrington of the SFPD, “Winston’s chief interest in the girls was to introduce them into the use of marijuana. Their sordid education in other fields was left to older women of the ‘academy.’” The lurid news reports noted that the girls were exploited by men as well as women, but it was the threat of homosexuality and gender nonconformity that transfixed public attention, not the possibility that sex trafficking of minors might be occurring.

The raid led to a State Board of Equalization hearing in December 1954 to determine whether to revoke the liquor license at Tommy’s Place and 12 Adler. The hearing was attended by over one hundred mothers, members of several local parent-teacher groups who were agitating for shutting down the two bars.

Details from the hearing, where teen girls took the stand to make statements about their experiences at Tommy’s Place, were breathlessly reported in the news.

The first witness was described in the San Francisco Chronicle as “A pretty 17-year-old girl, wearing the traditional sweater and skirt, saddle shoes and bobby socks.” When she said that she first started going to Tommy’s Place at thirteen, “The word ‘thirteen’ bubbled and spread through the room like a tide. ‘Thirteen’ one mother whispered to another.”

This girl admitted that she bought beer, cocktails, and bennies at Tommy’s Place, and she said that although a bartender once asked her how old she was, he accepted her word when she told him she was 21. She also admitted to buying marijuana at Winston’s Telegraph Hill flat, and to visiting other bars where she’d also bought drinks, including the lesbian bars Mona’s and Ann’s 440.

A second witness, described as “a pretty, tousle-haired 18-year-old girl,” started going to Tommy’s because her friend (the previous witness) had told her it was gay. According to the San Francisco Examiner:

A girl who admitted being a patron of Tommy’s Place at 17 lowered her head at a State hearing yesterday and used a term which fell from her lips like an obscene word. In a barely audible whisper, she said that Tommy’s Place had been recommended to her as a “gay” bar, meaning, she explained, a bar frequented by homo sexuals [sic].

She had also gone to other gay bars, including Mona’s, Ann’s 440, and the Beige Room, and started going to Tommy’s regularly in October 1953, where she bought bennies and beer. She admitted to visiting Winston’s apartment over a hundred times, where she bought marijuana. Under questioning, she also revealed that she was a reluctant witness, and had been told she could testify against the three women owners of Tommy’s Place as a juvenile, or go on trial herself as an adult.

One key detail in the Chronicle reporting struck me as particularly poignant: “With a half smile at the three women [Joyce Van de Veer, Grace Miller, and Jeanne Sullivan, who owned Tommy’s Place], she said they had not introduced her to Winston and did not know she bought benzedrine in the bar.” I wondered whether she had known the bar owners in a happier context. Had they welcomed her into a lesbian community? She seemed to be trying to show they had not broken any laws. What a humiliating and difficult experience it must have been to be forced to testify against them.

The Aftermath

Over several months after the initial raid, Winston, Miller, and Van de Veer went on trial. In November, Winston was convicted on three counts of furnishing marijuana to minor girls and one possession of marijuana. In December he was sentenced to San Quentin, where he served five years.

In December, following a jury trial, Van de Veer was acquitted of supplying minors with narcotics, but Miller was less fortunate. In 1955, Miller was found guilty of selling alcohol to minors and served six months in county jail. Reba Hudson, a friend of Miller’s and a community member who was interviewed by Boyd for Wide Open Town, said that “it was a terrible experience for her.”

Hudson also told Boyd that most people in the gay and lesbian community thought that the police had framed Tommy’s Place by planting the heroin:

Everybody figured, due to everything that was happening there at the time, that someone had planted the heroin. We didn’t know anyone who used heroin, and Grace, certainly, and Joyce, well, they were real nice. But it just didn’t make any sense for somebody to tape this stuff to a pipe beneath the sink because they certainly weren’t shooting up in there. It just would never have been wise. It wouldn’t even have been possible to do it, so everybody figured it was a police plant.

The Mattachine Society, a newly created homophile or gay rights organization, refuted the police charges in their newsletter:

The owners deny these charges. They have forced strict identification rules and have not tolerated the presence of any suspected or known drug addicts.

But the gay community’s denials made no difference. In 1955, the California legislature created the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board (ABC), which focused on fighting vice rather than generating revenue, and San Francisco elected Mayor George Christopher, who ran on an anti-vice platform. An aggressive campaign against queer spaces began.

Although Stoumen v. Reilly had decided that homosexuality as a state of being was legal, homosexual conduct, which could be anything from cross-dressing to acting stereotypically gay, was illegal. Police began to use undercover agents to entrap the patrons of gay bars.

In the face of this policing, gay bars still stayed defiantly open, but I think it’s not an accident that the late 1950s and early 1960s also saw the rise of a nascent gay rights movement in those homophile organizations. One of them, the Daughters of Bilitis, was initially formed to provide a safe space for lesbians to socialize outside the bars. In the 1960s, LGBTQ people began to demonstrate in the streets and push back against police raids, including at the 1965 Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco, and of course at the Stonewall riots in 1969.

At the start of Last Night at the Telegraph Club, Lily is not aware of the changing nature of policing on gay bars in San Francisco, or that the gay scene in the city is about to change. As a seventeen-year-old newly discovering the lesbian community, the Telegraph Club, which is a fictional version of lesbian bars like 12 Adler and Mona’s, is a space of freedom and wonder. Inside those walls, Lily can explore what it’s like to experience her desires openly, without shame. But part of her introduction into the lesbian community also involves learning how it was policed by both the police and the culture at large.

Postscript: Who was Tommy Vasu?

Tommy Vasu was born in Ohio around 1917-18 under a different name, and moved to San Francisco in the 1940s, where she opened the city’s first lesbian-owned bar, Tommy’s 299 Club, at 299 Broadway. Vasu was known in the community for wearing suits and ties, driving around the city in her Cadillac, and her beautiful blonde girlfriends.

Left to right: Unknown, Kay Caroll, Jeanne Sullivan, and Tommy Vasu at Mona’s Candlelight, circa 1949.

Lesbian community member and entertainer Pat Bond, in an interview with Allan Bérubé in 1981, described Tommy vividly:

[S]he made a lot of money and she would go with hookers a lot. And she would buy them fur coats and John Fredericks [sic] hats. [A]nything you wanted, Tommy could get it for you. You wanted a watch, she’d bring out forty watches. She liked being a gangster, like Frank Sinatra, that kind of [thing]. She was in drag from the time she was twelve. All her life.

After the raid on Tommy’s Place and 12 Adler, Vasu managed the Romolo parking lot at 530 Broadway until the mid-1960s. In 1969, Vasu was convicted of selling heroin, and served five years at Tehachapi State Prison in Vacaville. In 1978, when she was 61, Vasu was reportedly murdered in Los Angeles. I have been unable to find any sources documenting her murder.

In 1961, San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen described her as “the short-haired, long-tempered girl named Tommy who runs the best parking lot on B’way in North Beach—a gentleman among ladies.”

Support My Writing

I’ve been blogging about books, popular culture, diversity and inclusion, and LGBTQ+ issues since the early 2000s. If my writing makes your life more enjoyable or shows you a new perspective, please consider supporting my ability to write with a donation. Your support means the world to me.

References

Disclosure: Some links go to Bookshop.org, where I am an affiliate. If you click through and make a purchase, I will earn a commission.

Boyd, Nan Alamilla. Wide-Open Town :a History of Queer San Francisco to 1965. University of California Press, 2003.

Graves, Donna J., and Shayne E. Watson. Citywide Historic Context Statement for LGBTQ History in San Francisco. City and County of San Francisco, 2016.

View more posts in the Notes From the Telegraph Club series