The other day on twitter I saw someone tweet about their reluctance to read f/f (female/female) romance, even though they identified as a queer woman. They admitted that reading f/f could somehow feel too close for comfort; that reading m/m (male/male) romance was sometimes easier, and allowed them to relax more. Several people responded, a bit self-consciously, that they agreed.

Read MoreEvery year since 2009, I’ve written an annual review of what I did in the past year and what I'm looking forward to in the next. These posts are all here on my website if you want to take a look back. Here’s my review for this most recent turn around the sun.

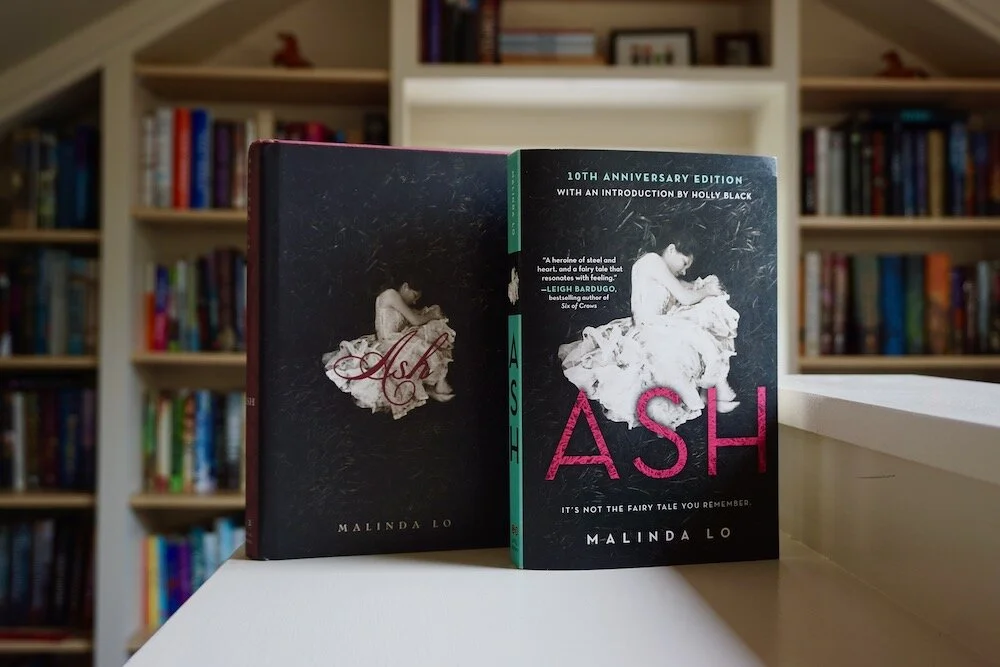

Read MoreMy first novel, Ash, was published in September 2009, which means this year marks my tenth year as a published novelist. Over the last few months I’ve tweeted out some of the lessons I’ve learned in the past decade, and as 2019 draws to a close I wanted to gather those lessons together in a more archivable format. These lessons come from my experience in traditional young adult publishing. Writers who are published in other genres, age categories, or who are self-published may have differing experiences.

Read MoreThe word important and how it’s applied to children’s and young adult books—especially “diverse books,” which is the way the publishing industry has come to describe books about marginalized characters, e.g. characters who are of color, LGBTQ, disabled, and/or from a marginalized religion—has been bothering me for some time. All of my books are about queer girls, and some of them are also Asian. My books have often been described as “important,” and while I understand that this is meant to be a compliment, it’s one that often grates on me.

Read MoreA couple of months ago, the New York Times asked me if I’d be interested in writing some flash fiction (that is, a very short story) inspired by a photo from their archives. This story would be part of a collection of flash fiction written by Asian American young adult authors. You don’t get this kind of invitation every day (!) so of course I said yes.

The Times then sent me a selection of photos from their archives, and I chose one of them that inspired me. It was, I admit, the strangest and quirkiest photo they sent me. I knew that the flash fiction collection was aiming to explore Asian American identity, and because I’m a contrarian and delight in pushing against identity boxes, I chose the photo that seemed to be the least connected to popular concepts of “Asian American identity.”

Read MoreNo matter how many charts I make, none of them tell me anything about how good a book is. Obviously, individual taste varies, and no book is for every reader, but there is a way to assess which books are judged to be of high quality: examining the top awards for LGBTQ YA books.

Every year, books that are considered high quality by certain experts in the field are given awards. Within the young adult category, the most prestigious American awards are the Printz Award, given by the American Library Association, and the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, given by the National Book Foundation. These awards don’t focus on LGBTQ characters or issues, but in the past they have been given to books about LGBTQ characters or issues; for example, I’ll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson (Dial), won the Printz in 2015; and We Are Okay by Nina La Cour (Dutton) won the Printz in 2018.

Additionally, several awards focus specifically on books about LGBTQ characters. The American Library Association’s Stonewall Book Award, which began as the Gay Book Award in 1986, started to honor LGBT children’s and young adult books in 2010. The Lambda Literary Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting LGBTQ literature, established the Lambda Literary Awards in 1988. They began recognizing LGBT children’s and young adult books in 1992.

Read More